Of the 120,000 honoured in the Books of Remembrance on Parliament Hill, one is the grandfather’s brother I never had a chance to meet.

Article content

Hello, Great Uncle George.

We never met in person. You were a younger brother of my grandfather, but you died exactly 109 years ago, nearly two decades before my own father was born and a half-century before I drew my first breath.

The reason I’m writing now is that I’ve been reading, and learning, a lot more about you.

That includes things like your only-months-long service in Canada’s army in the First World War, your capture and subsequent death in a prisoner-of-war camp on June 1, 1915, and the location of your grave near Kassel, Germany, a couple of hours’ drive northeast of Frankfurt.

Advertisement 2

Story continues below

Article content

Those facts help explain how you came to be one of more than 120,000 Canadian war dead with engraved places of honour in the Memorial Chamber on Parliament Hill. A cousin from British Columbia tipped me off to your place in national history.

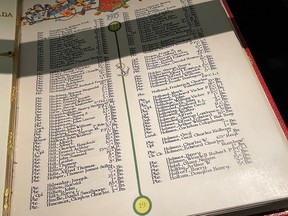

I saw it for myself a few months ago, on Jan. 22. It’s on that date, every year, that your name and those of 125 or so other war dead from 2015 are displayed on Page 19 of the First World War Book of Remembrance.

A daily ceremony to turn over pages in that volume — and others in the collection of eight overall now — takes place on the lower level of West Block, one of the first buildings to be refinished in the years-long rehabilitation of historic edifices on Parliament Hill, including the Centre Block’s Peace Tower, where the Memorial Chamber was previously housed.

I made my appointment to view the ceremony through the office of the House of Commons Sergeant-at-Arms.

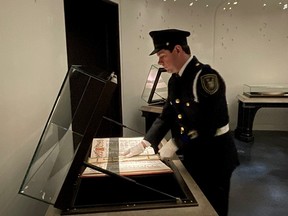

Moments before it began, a security officer opened locks and raised protective covers for five books.

Precisely at 11 a.m., under small ceiling lights like stars in the night sky, a constable in dress uniform and white gloves — to protect the pages — turned over Page 17 of the First World War book, displaying pages 18 and 19. There you were.

Advertisement 3

Story continues below

Article content

The constable continued on, with precise, deliberate steps positioning him in front of each volume before he’d reach in, carefully turn the respective pages and then replace decorative bookmarks. Each time he stepped back and saluted.

I stood silently near the chamber’s entrance, taking photos.

Those memorial books less populated than yours don’t have pages turned daily, but rather on a well-established rotation. For Jan. 22, the constable attended to books for Newfoundland before Confederation, the Merchant Navy, the War of 1812 and one titled “In the Service of Canada” for those who have perished since Oct. 1, 1947, other than in the Korean War.

With names of more than 66,000 fallen Canadians from 1914-18, the First World War Book of Remembrance contains 55 per cent of the overall toll. Second-most, at nearly 45,000, is the Second World War from 1939-45.

Other volumes contain only fractions of that: 516 for the Korean War (1950-53); 1,600 for the War of 1812 (1812-15); almost 300 combined for the Nile Expedition (1884-85) and South African War (1899-1902); more than 2,300 for Newfoundland and a separate 2,100 from the Merchant Navy in the two world wars; and more than 1,900 “In the Service of Canada.”

Advertisement 4

Story continues below

Article content

Upon departure, I received an envelope from the Sergeant-at-Arms’ office containing a letter and high-resolution miniatures of your Book of Remembrance inside cover and Page 19.

All of this ignited a spark of curiosity, so I conducted my online research blitz, finding the George Henry Holder military records file on a Library and Archives Canada website.

* Born in Manchester, England: my grandfather, Thomas Bing Holder, was born there, too, in 1884.

* Birthdate: Dec. 21, 1895, according to military documents, but Dec. 21, 1896, in an International Red Cross prisoner-of-war report. So, did you lie about your age, claiming to be 18, when you enlisted at Minnedosa, Man., on Aug. 22, 1914? Or was that simply a misreading of handwriting?

* Sept. 10, 1914: Freshly enlisted in the 12th Manitoba Dragoons, three months before either your 18th or 19th birthday, you passed a physical exam at Valcartier, Que.

* Oct. 8, 1914: Five days after starting to sail overseas, you were transferred to the 5th Battalion, Saskatchewan Regiment, of the Canadian Infantry.

* April 24 or 25, 1915: You took a bullet in the left leg at St-Julien, Belgium, according to both military records and the Red Cross report, though there’s a one-day discrepancy in when that actually occurred. There were also two references to “août,” or August, clearly in error.

Advertisement 5

Story continues below

Article content

* May 1, 1915: You arrived at POW camp in Ohrdruf, a town in the German state of Thüringen, or Thuringia in English. After displaying symptoms of tetanus, you received curing serum injections, but a few weeks later developed pyelonephritis, a bacterial infection that led to inflammation in the kidneys.

* June 1, 1915: According to the Red Cross, unable to take nourishment for several days previous, you died at 11:45 a.m. It was a Tuesday. Your personal effects included a comb and a pocketbook with a military booklet. Medics then discovered a tumour on your pancreas, surprising since you had been listed as a non-smoker and abstainer at the time of enlistment less than 10 months earlier.

The Memorial Cross page in the records showed your father, Joseph Holder, would have received a Plaque and Scroll official recognition piece, given to families of British Empire service members who died in the First World War, while your mother, Mary Ann, would have been presented with a Cross of Sacrifice medal presented to widows or mothers of fallen Canadians.

The same documents say your grave is in Niederzwehren Cemetery, 10 kilometres south of Kassel and two kilometres from the main road to Marburg.

Advertisement 6

Story continues below

Article content

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission has only general images of that cemetery, but one of its representatives helpfully relayed a contact to The War Graves Photographic Project, also U.K.-based, and that led to a high-quality photo of the headstone bearing the name G.H. Holder and your Regimental Number: 13421.

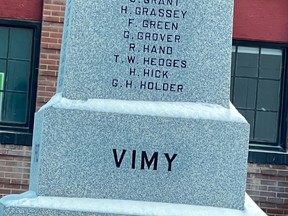

You’re also memorialized “back home” in Minnedosa, Man., where your family settled down after emigrating from England. Proof of that came in photos of the town cenotaph courtesy of the Minnedosa Regional Archives.

My own family from Brandon, roughly 50 kilometres away, spent many summer days and weeks in Minnedosa during my youth, and I remember the cenotaph being there, but admittedly I’d never inspected it well enough to spot “G.H. Holder” on one side, between the “H. Hick” listing for farmer Hubert Hick and the larger “Vimy,” an inscribed tribute to the great Canadian military triumph nearly two years after you died.

Admittedly it sounds odd that I’ve only now picked up all these details, but my father and his two surviving brothers — the youngest of them 88, the oldest 92 — are similarly in the dark. One thinks you might be seen in their parents’ wedding photo, before enlistment, but that’s pretty much it.

Advertisement 7

Story continues below

Article content

Another link has turned up, though. William and Mary Holder—who after your death received the “assigned pay” of $162 ($18 each for nine months of service) and not your parents Joseph and Mary Ann—had a son named George Edwin Holder in October 1923.

So here’s the summary: My 5-foot-7, 150-pound great uncle enlisted in Canada’s army at either 18 or 17, was injured, captured and died in a German prisoner-of-war camp. You hadn’t yet turned 20, or possibly even 19.

Your sacrifice is noted and honoured.

Our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark our homepage and sign up for our newsletters so we can keep you informed.

Recommended from Editorial

Article content

Comments