In a packed North Bay, Ont. auditorium this March, residents, environmental and legal aid groups gathered to discuss a problem that’s been decades in the making, and that risks affecting not only those who live in the area, but likely millions more Canadians across the country.

The public information session’s focus was PFAS, a kind of artificial, potentially toxic chemicals that have crept into countless corners of daily life, and of which many persist in the land, water and human body alike for years.

Since as far back as the 1970s, North Bay’s municipal water supply in nearby Trout Lake has harboured PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), which Health Canada notes have been associated in some cases with liver and developmental issues, cancer and complications with pregnancy.

In recent weeks, U.S. regulators have finalized new maximum limits on six key kinds of PFAS in drinking water, and in Canada, a new proposed limit of 30 parts per trillion is pending for waterborne PFAS as a whole; one that North Bay’s water often exceeds in municipal testing.

“We’re really fortunate to have this abundant supply of cold, clear water, and I think that knowing that it’s got this very persistent contaminant in it … potentially interferes with all our relationships with that water,” said Brennain Lloyd of Northwatch, a local organizer of the information session, in an interview with CTVNews.ca.

“That’s a tragedy that can’t be measured.”

Also known as ‘forever chemicals,’ PFAS are built from some of the strongest bonds of their kind found in nature, meaning they likely won’t go away on their own. And the path to ridding them from the environment is a long and expensive one for a local government with limited resources and an understandably concerned populace.

As far as Canadian cities go, North Bay’s problem is far from the only one.

Non-stick sticks around

First developed in the 1930s and ’40s, PFAS are effective at creating waterproof and non-stick properties, and can be found in a litany of products.

Everything from cosmetics, to cookware, to electronic devices can carry PFAS, and as those products degrade through routine wear, tear and disposal, tiny particles of them can accumulate in earth, water and air, as well as within the body.

Stain resistant carpets and upholstery, cosmetics, waterproof clothing, takeout containers and non-stick cookware are all examples of potentially PFAS-treated products. (Charlie Buckley / CTV News)

Stain resistant carpets and upholstery, cosmetics, waterproof clothing, takeout containers and non-stick cookware are all examples of potentially PFAS-treated products. (Charlie Buckley / CTV News)

“Every day, you’re coming in contact with PFAS,” said Miriam Diamond, an environmental chemist at the University of Toronto, in an interview with CTVNews.ca. “You wouldn’t know where it is, because it’s not listed on labels.”

Diamond’s research has studied potential points of exposure to forever chemicals in food packaging, cosmetics and possibly even the paint found on some playground equipment. To hear her tell it, trying to avoid them is a challenge.

“Half the [food] packaging that we tested had PFAS in it to achieve grease and water repellency,” she said. “The good news is that half didn’t, but you don’t know which half; we have no idea.”

A PFAS particle that began its life in the waterproof coating on a takeout container could find its way from the dirt of a landfill, down a nearby stream, into the body of a fish and eventually a person — that is, if it didn’t get to them already through the air and water themselves, or the takeout served in that container in the first place.

An international study published last month found PFAS to be “pervasive in [surface and ground water] worldwide,” with 69 per cent of samples exceeding concentration limits proposed by Health Canada, even when a specific source of contamination could not be identified.

According to the local government, North Bay’s PFAS problem came to be in part due to something outside the control of any individual resident: Jack Garland Airport, located upstream from Trout Lake.

Among the many safety features found at modern airports are crash trucks; fire prevention vehicles equipped with specialized, extinguishing foam that often contains PFAS.

Among the many safety features found at modern airports are crash trucks; fire prevention vehicles equipped with specialized, extinguishing foam that often contains PFAS.

As that foam has been released during emergencies, or in the years of firefighter training that the airport grounds hosted in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, it has seeped into the soil and into Lee’s Creek, a waterway connected to Trout Lake, across a small bay from the local water treatment plant.

“The key to this is it doesn’t break down,” Diamond explained. “Hence the situation now, where millions of people worldwide are exposed to elevated levels of PFAS in their drinking water … communities beside military operations and airports are particularly at risk.”

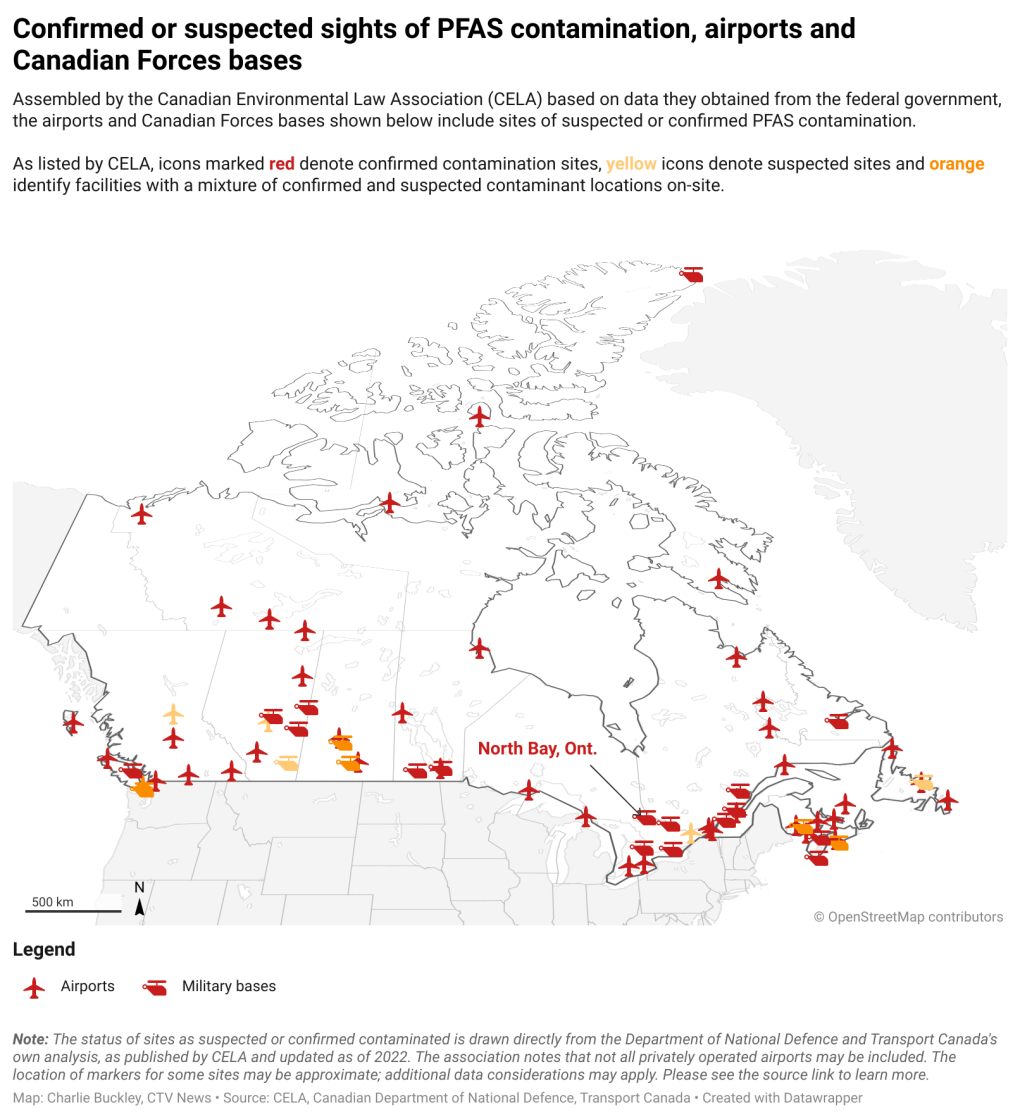

In 2021, Northwatch, the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA) and others filed a petition to the federal government asking about its response to PFAS and last year, CELA released a list of more than 100 sites identified by the Department of National Defence (DND) and Transport Canada as suspected or confirmed to be contaminated, an association release reads.

Updated as of 2022, the list contains sites at many of Canada’s major airports, as well as Canadian Forces facilities across 10 provinces and territories.

Source: CELA, Canadian Department of National Defence, Transport Canada

Source: CELA, Canadian Department of National Defence, Transport Canada

This February, the City of North Bay announced plans to begin remediation of the PFAS contamination at Jack Garland Airport this year, paid for with nearly $20 million in federal funding from the Department of National Defence.

“We are extremely pleased that cleanup efforts at the airport site are now about to get underway,” said North Bay Mayor Peter Chirico, in a release. “Our priority throughout this process is and has been the health and safety of our residents.”

Similar remediation efforts have been announced elsewhere.

“We have a responsibility to work with cities and provinces to safeguard the health of Canadians,” said Defence Minister Bill Blair in a November press release, announcing millions more in federal funding to address PFAS concentrations linked to CFB Bagotville, near Saguenay, Que.

“We will continue to collaborate with the city and Quebec to protect the health and safety of local residents.”

Chemical concerns

Once PFAS enter the body, some kinds can take months or years to leave, meaning forever chemicals can build up, or what scientists call bioaccumulate, over a person’s lifetime. And with so many potential sources of exposure, population-level monitoring by Health Canada has found the presence of PFAS to be extremely common among Canadians.

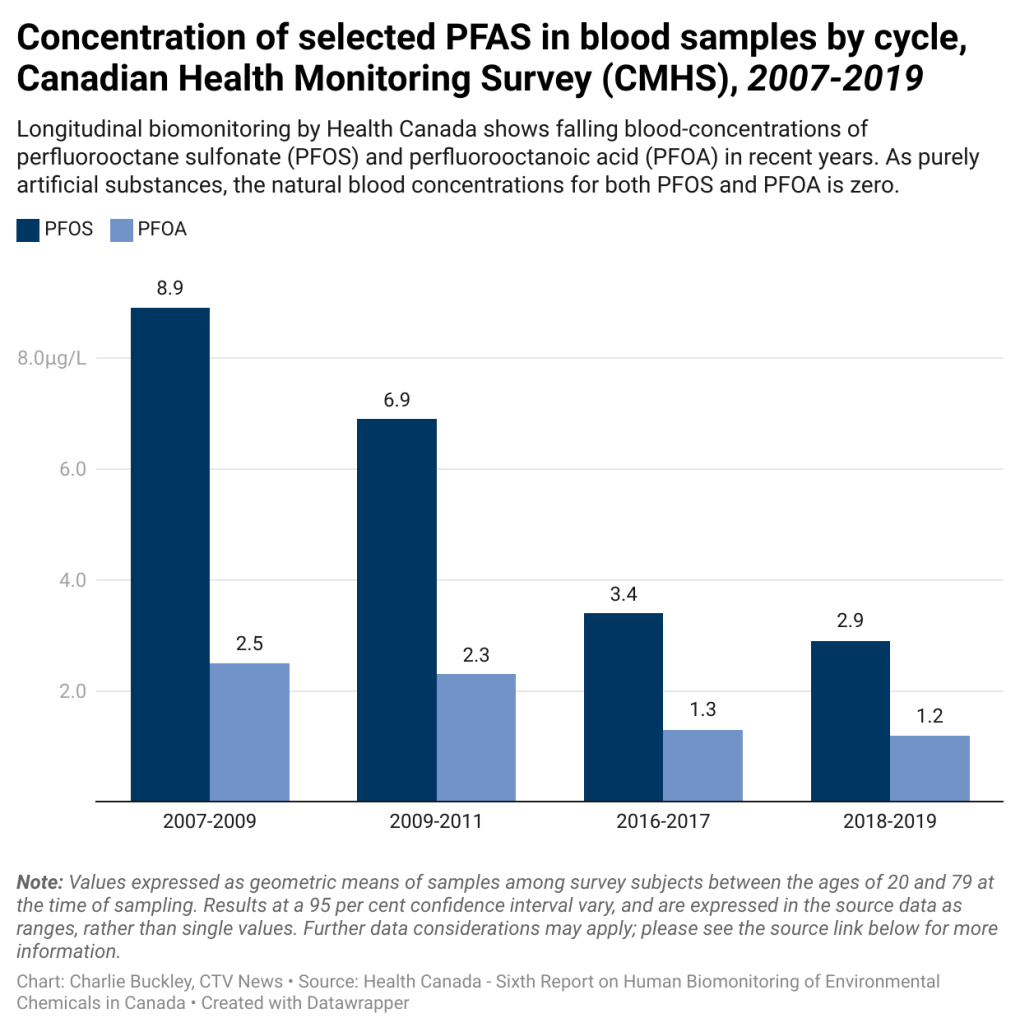

As of the 2018-19 study cycle, the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) found perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), a type of PFAS, in 99.3 per cent of tested blood samples from Canadians aged three to 79. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), another variety, was detected in 100 per cent of samples.

Health Canada notes that exposure to some kinds of PFAS has been linked with a variety of health risks, including to the nervous, endocrine, immune and reproductive systems. PFOA in particular has been recognized by international authorities as a possible carcinogen.

One analysis published in 2022 found that in the United States alone, PFAS-related illness could account for US$5.52 billion in medical costs and lost productivity in 2018; an estimate the study authors describe as “highly conservative.”

The news isn’t all bad. Longitudinal monitoring by Health Canada shows that blood concentrations for some of the most notorious kinds of PFAS have been decreasing, in recent years.

In the 2007-09 sampling cycle of the CHMS, the average concentrations of PFOS and PFOA were just over eight and two micrograms per litre, respectively, but by 2018-19, they had fallen 67 and 52 per cent.

U of T’s Diamond notes that, while this can be taken as encouraging, those numbers only account for two of the thousands of different PFAS chemicals known to scientists, and while PFOS and PFOA have drawn down in response to years of targeted policy change, their chemical cousins, of which information is far less available, have grown in use.

U of T’s Diamond notes that, while this can be taken as encouraging, those numbers only account for two of the thousands of different PFAS chemicals known to scientists, and while PFOS and PFOA have drawn down in response to years of targeted policy change, their chemical cousins, of which information is far less available, have grown in use.

And even for those waning PFAS varieties, the story isn’t over yet.

“We still have PFOS and PFOA in us, after implementing first controls in 2006 and 2008,” she said. “That tells us how long it takes for levels to go down.”

‘It’s everywhere’

In the past, government action to fight PFAS has been fairly surgical, targeting individual subgroups of chemicals. But to Diamond, the far more effective strategy is to restrict PFAS as a single, broad category and work backwards to exempt some essential uses, as needed.

“Deal with them as a class, so it’s not whac-a-mole,” Diamond said. “We cannot figure out the toxicity of all of them. We do know that some are toxic. Their high persistence in the environment is enough for me to recommend restriction, without waiting for proof of toxicity.”

It’s a move the federal government has shown interest in pursuing. In May 2023, Environment and Climate Change Canada announced moves toward proposing that “all substances in the class of PFAS have the potential to cause harm to both the environment and human health.”

“Based on emerging science and what is known about well-studied PFAS, a proactive and precautionary approach is needed to help address these substances as a class,” said Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault, in a release.

Diamond envisions a system of required drawdowns in PFAS use across many industries, timed to allow a window for manufacturers to find non-PFAS alternatives, as the outdoor apparel and other select industries have begun to do. That push for innovation that has found its way to airport firefighting, as well, she notes.

Airports around the world, including those all across Australia, have transitioned to PFAS-free foams, and recently, Toronto’s Billy Bishop Airport became the first in North America to make the switch, according to its new non-PFAS foam supplier.

But even if the flow of new contaminants were to be stemmed, there still remains a great deal of existing PFAS to address in communities like North Bay.

Bringing down those concentrations could mean expensive retrofits at local treatment plants, individualized supports for residents on well water and lengthy clean-ups that millions of dollars in pledged federal funding may not be enough to accomplish.

To Northwatch’s Brennain Lloyd, who has lived steps away from Trout Lake for more than three decades, one of the first steps to solutions is to get the word out.

“That meeting in the North Bay Library auditorium, filled to overflowing, really said: ‘People want to know about it,'” she said.

“They want to know about the issue and they want to know what the response is.”

Edited by CTVNews.ca Special Projects Producer Phil Hahn